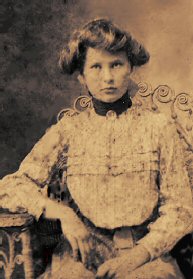

After discovering her parents and younger siblings had been attacked, Addie awoke her two other sisters, and together they worked quickly to extinguish the smoldering flames. Then, carrying six-year-old Alice, still barely alive, all three set out to find help from a neighbor.

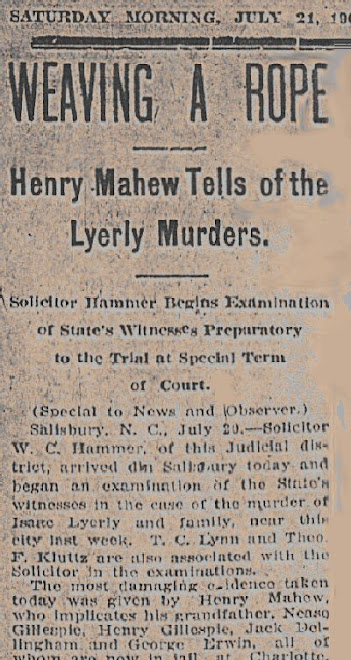

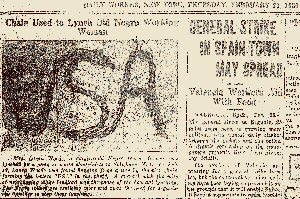

A message to the Salisbury sheriff, telegraphed from nearby Barber Junction railroad station, was soon heard round the country. And the media blitz began.

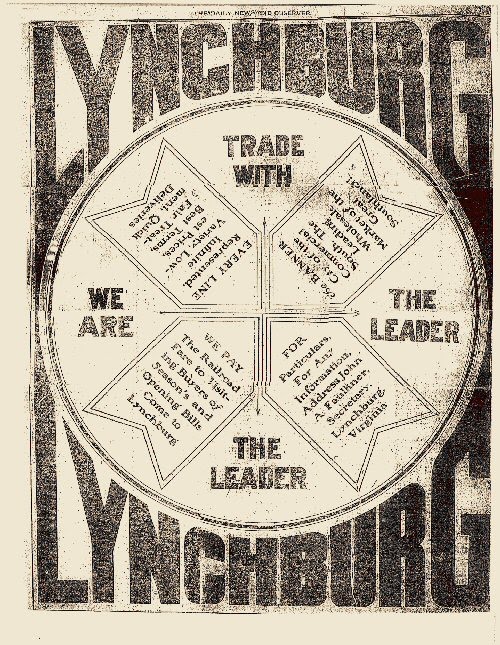

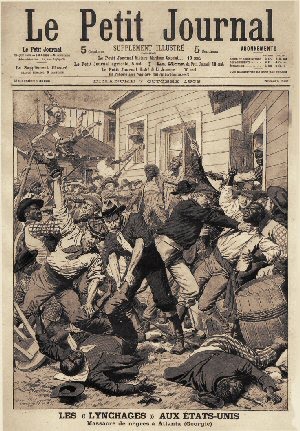

Even without embellishment, the facts of the Lyerly murders were enough to make the coldest blood boil. But they also presented the perfect opportunity for the newly-crowned Jim Crow-dominated press to justify its recent coup, which virtually rescinded the rights former slaves had barely begun to enjoy. It didn't take reporters from Charlotte and Salisbury long to lay blame for the murders on the Lyerly's tenant farmers, focusing on an argument over crop payment they'd had months earlier.

So, what started out as an investigation of the ax murders and lynching, turned into a study of early 20th century press as well – revealing how the majority of reporting in the South was contaminated by the political agenda of white supremacy.

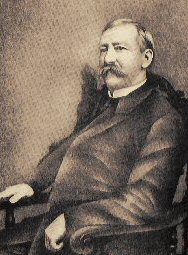

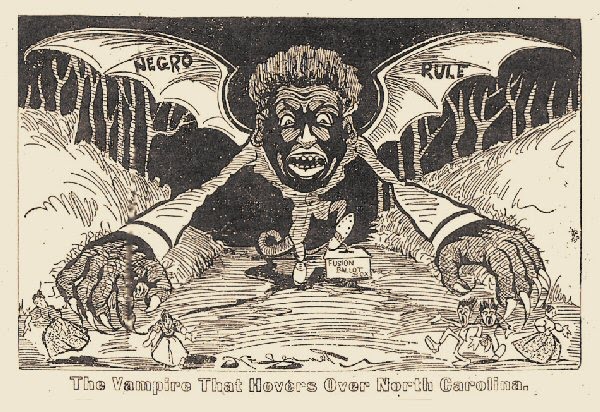

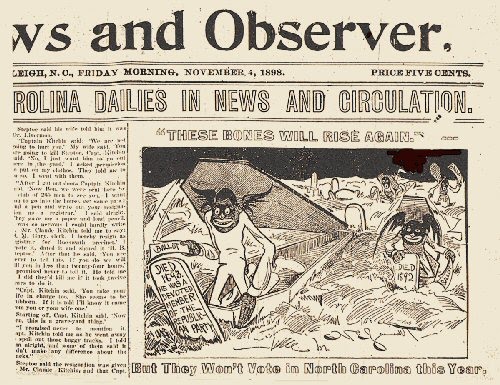

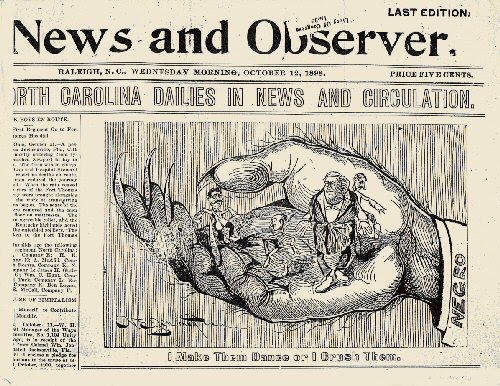

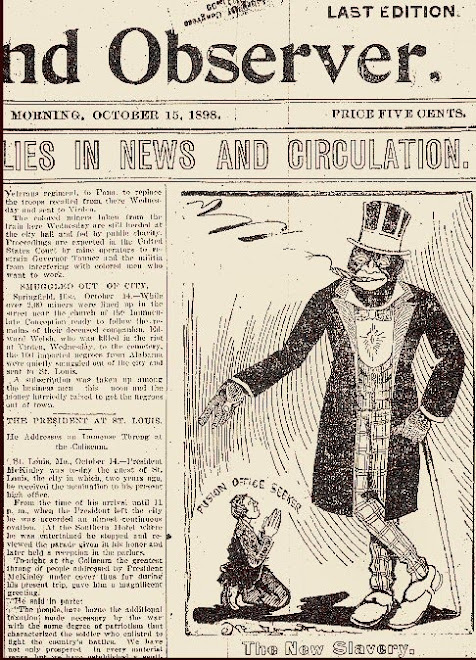

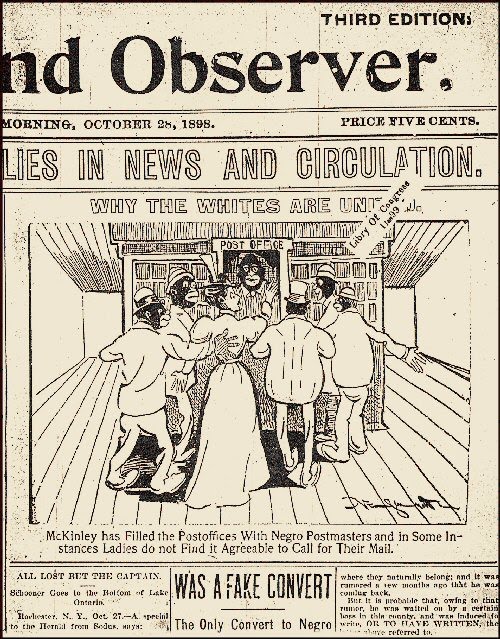

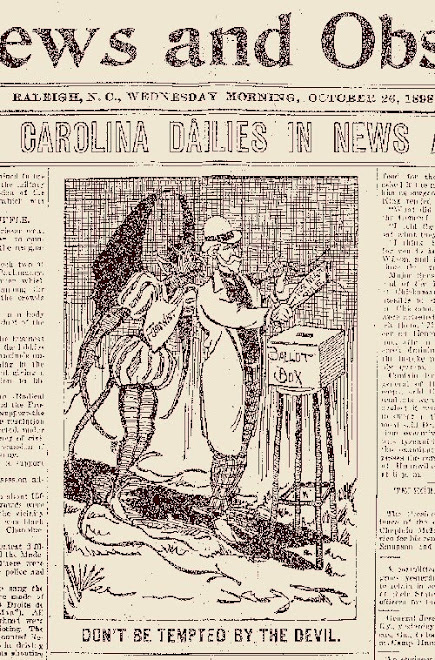

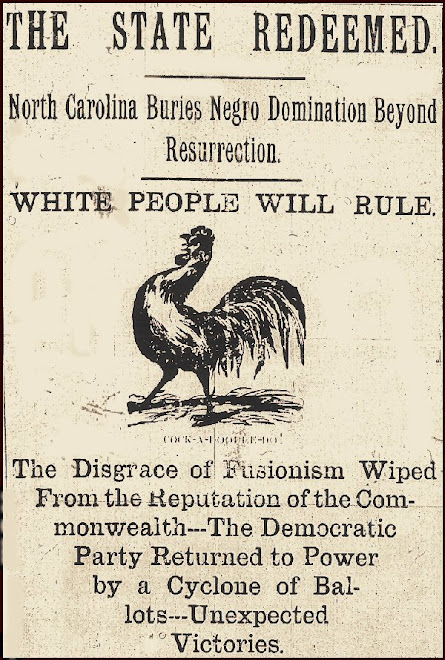

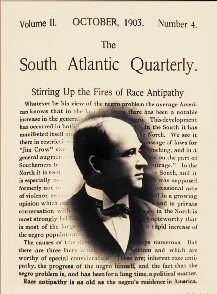

Named after the lynching games children played in the aftermath of the tragedies, A Game Called Salisbury is more than just the story of a regional tragedy. It serves to illustrate one of the more devastating residual effects of Raleigh News and Observer editor Josephus Daniels' 1898 white supremacist campaign tactics. Daniels, who went on to serve as Woodrow Wilson's Secretary of the Navy, dominated and contaminated most of North Carolina’s press with racist propaganda, creating much of the mindset on, and the myths of, "race" that remain intact today.

Future posts will include some of the images and tactics Daniels deployed to destroy the lives of African Americans and create his Jim Crow empire.

Addie Lyerly

Around midnight Friday, July 13, 1906, Addie, awakened by smoke, descended the stairs of her Rowan County home to find her parents and younger siblings drenched in blood and the bedroom on fire.

Saturday, March 20, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment